Monday, April 25, 2011

Sunday, April 25, 2010

ScienceDaily (Apr. 14, 2010) — Whether it's an exploding fireball in "Star Wars: Episode 3," a swirling maelstrom in "Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End," or beguiling rats turning out gourmet food in "Ratatouille," computer-generated effects have opened a whole new world of enchantment in cinema. All such effects are ultimately grounded in mathematics, which provides a critical translation from the physical world to computer simulations.

ScienceDaily (Apr. 14, 2010) — Whether it's an exploding fireball in "Star Wars: Episode 3," a swirling maelstrom in "Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End," or beguiling rats turning out gourmet food in "Ratatouille," computer-generated effects have opened a whole new world of enchantment in cinema. All such effects are ultimately grounded in mathematics, which provides a critical translation from the physical world to computer simulations.Mathematics provides the language for expressing physical phenomena and their interactions, often in the form of partial differential equations. These equations are usually too complex to be solved exactly, so mathematicians have developed numerical methods and algorithms that can be implemented on computers to obtain approximate solutions. The kinds of approximations needed to, for example, simulate a firestorm, were in the past computationally intractable. With faster computing equipment and more-efficient architectures, such simulations are feasible today -- and they drive many of the most spectacular feats in the visual effects industry.

Read more....

(Image credit: labspaces.net)

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

In the northern British Isles, the Celtic tribes known as the Picts coexisted for centuries alongside literate cultures such as the Romans, the Irish and the Anglo-Saxons.

In the northern British Isles, the Celtic tribes known as the Picts coexisted for centuries alongside literate cultures such as the Romans, the Irish and the Anglo-Saxons."They were the odd society out, in that they didn't leave any written record," says Rob Lee of the University of Exeter in England, save for some mysterious-looking sets of symbols on stones and jewels. In a paper published March 31 online in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, Lee and his coworkers now claim that the symbols are written language. Perhaps the Picts were not illiterate after all.

Lee's team attacked the problem with math. Written languages are distinguishable from random sequences of symbols because they contain some statistical predictability. The typical example is that, in the English language, a "q" is nearly certain to be followed by a "u"; and a "w" is much more likely to be followed by an "h" than, say, by an "s" or a "t".

Read more....

Saturday, March 20, 2010

SINCE “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” was published, in 1865, scholars have noted how its characters are based on real people in the life of its author, Charles Dodgson, who wrote under the name Lewis Carroll...

SINCE “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” was published, in 1865, scholars have noted how its characters are based on real people in the life of its author, Charles Dodgson, who wrote under the name Lewis Carroll...

But Alice’s adventures with the Caterpillar, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat and so on have often been assumed to be based purely on wild imagination. Just fantastical tales for children — and, as such, ideal material for the fanciful movie director Tim Burton, whose “Alice in Wonderland” opened on Friday.

Yet Dodgson most likely had real models for the strange happenings in Wonderland, too. He was a tutor in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, and Alice’s search for a beautiful garden can be neatly interpreted as a mishmash of satire directed at the advances taking place in Dodgson’s field.

In the mid-19th century, mathematics was rapidly blossoming into what it is today: a finely honed language for describing the conceptual relations between things. Dodgson found the radical new math illogical and lacking in intellectual rigor. In “Alice,” he attacked some of the new ideas as nonsense — using a technique familiar from Euclid’s proofs, reductio ad absurdum, where the validity of an idea is tested by taking its premises to their logical extreme.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

ScienceDaily (Mar. 10, 2010) — With pitchers and catchers having recently reported to spring training, once again Bruce Bukiet, an associate professor at NJIT, has applied mathematical analysis to compute the number of games that Major League Baseball teams should win in 2010. The Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Dodgers should all repeat as winners in their divisions, while the Atlanta Braves will take the wild card slot in the National League (NL), says Bukiet.

ScienceDaily (Mar. 10, 2010) — With pitchers and catchers having recently reported to spring training, once again Bruce Bukiet, an associate professor at NJIT, has applied mathematical analysis to compute the number of games that Major League Baseball teams should win in 2010. The Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Dodgers should all repeat as winners in their divisions, while the Atlanta Braves will take the wild card slot in the National League (NL), says Bukiet.Bukiet, an associate professor of mathematical sciences and associate dean of the College of Science and Liberal Arts at NJIT, bases his predictions on a mathematical model he developed in 2000. For this season, he incorporated a more realistic runner advancement model into the algorithm.

Read more....

(Image credit: topendsports.com)

Monday, March 8, 2010

ScienceDaily (Mar. 3, 2010) — A straight line may be the shortest path from A to B, but it's not always the most reliable or efficient way to go. In fact, depending on what's traveling where, the best route may run in circles, according to a new model that bucks decades of theorizing on the subject. A team of biophysicists at Rockefeller University developed a mathematical model showing that complex sets of interconnecting loops -- like the netted veins that transport water in a leaf -- provide the best distribution network for supplying fluctuating loads to varying parts of the system. It also shows that such a network can best handle damage.

ScienceDaily (Mar. 3, 2010) — A straight line may be the shortest path from A to B, but it's not always the most reliable or efficient way to go. In fact, depending on what's traveling where, the best route may run in circles, according to a new model that bucks decades of theorizing on the subject. A team of biophysicists at Rockefeller University developed a mathematical model showing that complex sets of interconnecting loops -- like the netted veins that transport water in a leaf -- provide the best distribution network for supplying fluctuating loads to varying parts of the system. It also shows that such a network can best handle damage.

The findings could change the way engineers think about designing networks to handle a variety of challenges like the distribution of water or electricity in a city.

Operations researchers have long believed that the best distribution networks for many scenarios look like trees, with a succession of branches stemming from a central stalk and then branches from those branches and so on, to the desired destinations. But this kind of network is vulnerable: If it is severed at any place, the network is cut in two and cargo will fail to reach any point "downstream" of the break.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

ScienceDaily (Mar. 1, 2010) — Kerry Whisnant, Iowa State University physicist, studies the mysteries of the neutrino, the elementary particle that usually passes right through ordinary matter such as baseballs and home-run sluggers.

ScienceDaily (Mar. 1, 2010) — Kerry Whisnant, Iowa State University physicist, studies the mysteries of the neutrino, the elementary particle that usually passes right through ordinary matter such as baseballs and home-run sluggers. Kerry Whisnant, St. Louis Cardinals fan, studies the mathematical mysteries of baseball, including a long look at how the distribution of a team's runs can affect the team's winning percentage.

Whisnant, a professor of physics and astronomy who scribbles the Cardinals' roster on a corner of his office chalkboard, is part of baseball's sabermetrics movement. He, like other followers of the Society for American Baseball Research, analyzes baseball statistics and tries to discover how all the numbers relate to success on the field.

The results are ideas, analyses, formulas and papers that dig deep into the objective data.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

The connection between music and mathematics has fascinated scholars for centuries. More than 200 years ago Pythagoras reportedly discovered that pleasing musical intervals could be described using simple ratios.

The connection between music and mathematics has fascinated scholars for centuries. More than 200 years ago Pythagoras reportedly discovered that pleasing musical intervals could be described using simple ratios.And the so-called musica universalis or "music of the spheres" emerged in the Middle Ages as the philosophical idea that the proportions in the movements of the celestial bodies -- the sun, moon and planets -- could be viewed as a form of music, inaudible but perfectly harmonious.

Now, three music professors – Clifton Callender at Florida State University, Ian Quinn at Yale University and Dmitri Tymoczko at Princeton University -- have devised a new way of analyzing and categorizing music that takes advantage of the deep, complex mathematics they see enmeshed in its very fabric.

Writing in the April 18 issue of Science, the trio has outlined a method called "geometrical music theory" that translates the language of musical theory into that of contemporary geometry. They take sequences of notes, like chords, rhythms and scales, and categorize them so they can be grouped into "families."

Read more....

Creativity in mathematics

Mathematics and Mime

In "Envisioning the Invisible", Tim Chartier describes how the performing arts can be used to capture mathematical concepts...In one of Chartier's mime sketches, he gets the audience to visualize the one-dimensional number line as a rope of infinite length.....Mathematics and Music

How does the brain sometimes fool us when we listen to music, and how have composers used such illusions?....How can math help create new music?...

Mathematics and Visual Art

...The forms emerging from this iterated function system are fractals. By serendipity, the article on music by Don et al employs some of Barnsely's work on fractal images to produce new music. Using Barnsley's Iterated Function Systems formulas, the authors created fractal images of a fern and of Sierpinski's triangle and used these images to create notes for musical compositions...

Read more....

Sunday, February 7, 2010

The Egyptians supposedly used it to guide the construction the Pyramids. The architecture of ancient Athens is thought to have been based on it. Fictional Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon tried to unravel its mysteries in the novel The Da Vinci Code.

The Egyptians supposedly used it to guide the construction the Pyramids. The architecture of ancient Athens is thought to have been based on it. Fictional Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon tried to unravel its mysteries in the novel The Da Vinci Code."It" is the golden ratio, a geometric proportion that has been theorized to be the most aesthetically pleasing to the eye and has been the root of countless mysteries over the centuries. Now, a Duke University engineer has found it to be a compelling springboard to unify vision, thought and movement under a single law of nature's design.

Also know the divine proportion, the golden ratio describes a rectangle with a length roughly one and a half times its width. Many artists and architects have fashioned their works around this proportion. For example, the Parthenon in Athens and Leonardo da Vinci's painting Mona Lisa are commonly cited examples of the ratio.

(Image credit: yorgos.ca)Wednesday, February 3, 2010

T

hanks to medical imaging techniques such as X-ray CT, ultrasound imaging and MRI, doctors have long been able to see to varying degrees what's going on inside a patient's body, and now a Texas A&M University mathematician is trying to find new and better ways to do so.

hanks to medical imaging techniques such as X-ray CT, ultrasound imaging and MRI, doctors have long been able to see to varying degrees what's going on inside a patient's body, and now a Texas A&M University mathematician is trying to find new and better ways to do so.The professor, Peter Kuchment, a leading researcher in mathematical techniques for medical imaging, says the research may enhance the process for detecting cancer and many other diseases.

When talking about medical imaging, most people know that physics and computer sciences are involved, but few may be aware that mathematics is indispensable. Indeed, many imaging methods are based on mathematical analysis.

(Image credit: tutorvista.com)

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

WildAboutMath by Sol-I became a big fan of Marcus du Sautoy when I read his books Symmetry, and Music of the Primes. From that video I learned about du Sautoy’s fundraising page for Common Hope:

WildAboutMath by Sol-I became a big fan of Marcus du Sautoy when I read his books Symmetry, and Music of the Primes. From that video I learned about du Sautoy’s fundraising page for Common Hope: Common Hope promotes hope and opportunity in Guatemala, partnering with children, families, and communities who want to participate in a process of development to improve their lives through education, health care, and housing.

And I learned how to get my own symmetrical object:

What a great idea! So, I donated and now I’m the proud owner of a symmetry group. This could be the perfect gift for the Math lover who has everything...People have stars named after them, craters on the moon, even comets…but how about naming a symmetrical object in hyperspace. For a donation of over $10 you can have a new symmetrical object named after you or a friend. A great birthday present. My new book FINDING MOONSHINE (UK) or SYMMETRY (US) narrates the discovery of these new symmetrical objects that have interesting connections with objects in number theory called elliptic curves. Here is the chance to claim one of these groups and have the group named after you. I have created infinitely many of these groups so they won’t run out!

Read more....

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Like a lot of humans, monkeys might not be able to do calculus. But a new study shows that they can learn and rapidly apply abstract mathematical principles.

Like a lot of humans, monkeys might not be able to do calculus. But a new study shows that they can learn and rapidly apply abstract mathematical principles.Previous work has shown that monkeys and birds can count, but flexible applications of higher mathematic rules, the study authors asserted, "require the highest degree of internal structuring"—one thought largely to be the domain of only humans.

So researchers based at the Institute of Neurobiology at the University of Tubingen in Germany set out to see whether rhesus monkeys could learn and flexibly apply the greater-than and less-than rule. They tested the monkeys with groups of both ordered and random dots, many of which were novel combinations to ensure that the subjects couldn't have simply memorized them. The monkeys were cued into applying either the greater-than or less-than rule by the amount of time that elapsed between being shown the first and second group of dots.

"The monkeys immediately generalized the greater than and less than rules to numerosities that had not been presented previously," the two researchers, Sylvia Bongard and Andreas Nieder, wrote.

Read more....

Thursday, January 14, 2010

The mathematician who deciphered the final, encrypted page of a letter sent to President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 will visit the University of Oregon to tell how he did it.

The mathematician who deciphered the final, encrypted page of a letter sent to President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 will visit the University of Oregon to tell how he did it.The encrypted page -- a mystery to Jefferson and everyone else -- was solved in 2007 by Smithline, then 36, an expert in code-breaking. He detailed his solution in the American Scientist.

The letter was written by Jefferson's colleague in the American Philosophical Society, Robert Patterson, a math professor at the University of Pennsylvania. The ciphered page was devoid of capital letters or spaces and scrambled in a way that left no readable segments. Preceding pages had described the nature of the code but not the specific key required to unlock this message. The code was unlike any normally used at the time. Patterson predicted it would never be broken.

The solution involved both linguistic intuition and a computer algorithm to find the digital key. While the required 100,000 calculations would be easy on today's computers, Smithline's method could have been done over time in Patterson's day. In his talk, Smithline will tell how he was pulled into the mystery, how he broke the code and what was written on the page.Read more....

Emotional Bunny Says: "What's that? In the wrong hands, this information could have been fatal? Ah. I wouldn't worry about that...."

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

Polynomials, the meat and potatoes of high-school algebra, are foundational to many aspects of quantitative science. But it would take a particularly enthusiastic math teacher to think of these trusty workhorses as beautiful.

Polynomials, the meat and potatoes of high-school algebra, are foundational to many aspects of quantitative science. But it would take a particularly enthusiastic math teacher to think of these trusty workhorses as beautiful.As with so many phenomena, however, what is simple and straightforward in a single serving becomes intricately detailed—beautiful, even—in the collective.

On December 5 John Baez, a mathematical physicist at the University of California, Riverside, posted a collection of images of polynomial roots by Dan Christensen, a mathematician at the University of Western Ontario, and Sam Derbyshire, an undergraduate student at the University of Warwick in England.

Polynomials are mathematical expressions that in their prototypical form can be described by the sum or product of one or more variables raised to various powers.

Read more....

Friday, December 25, 2009

ScienceDaily (Dec. 25, 2009) — A team of researchers has shown that some mathematical algorithms provide clues about the artistic style of a painting. The composition of colours or certain aesthetic measurements can already be quantified by a computer, but machines are still far from being able to interpret art in the way that people do.

ScienceDaily (Dec. 25, 2009) — A team of researchers has shown that some mathematical algorithms provide clues about the artistic style of a painting. The composition of colours or certain aesthetic measurements can already be quantified by a computer, but machines are still far from being able to interpret art in the way that people do.

How does one place an artwork in a particular artistic period?

The researchers have shown that certain artificial vision algorithms mean a computer can be programmed to "understand" an image and differentiate between artistic styles based on low-level pictorial information. Human classification strategies, however, include medium and high-level concepts.

Sunday, December 20, 2009

...Computers have become an extension of us: that is a commonplace now. But in an important way we may be becoming an extension of them, in turn. Computers are digital — that is, they turn everything into numbers; that is their way of seeing. And in the computer age we may be living through the digitization of our minds, even when they are offline: a slow-burning quantification of human affairs that promises or threatens, depending on your outlook, to crowd out other categories of the imagination, other ways of perceiving.

...Computers have become an extension of us: that is a commonplace now. But in an important way we may be becoming an extension of them, in turn. Computers are digital — that is, they turn everything into numbers; that is their way of seeing. And in the computer age we may be living through the digitization of our minds, even when they are offline: a slow-burning quantification of human affairs that promises or threatens, depending on your outlook, to crowd out other categories of the imagination, other ways of perceiving.Welcome to the Age of Metrics — or to the End of Instinct. Metrics are everywhere. It is increasingly with them that we decide what to read, what stocks to buy, which poor people to feed, which athletes to recruit, which films and restaurants to try. World Metrics Day was declared for the first time this year.

The once-mysterious formation of tastes is becoming a quantitative science, as services like Netflix and Pandora and StumbleUpon deploy algorithms to predict, and shape, what we like to watch, listen to and read.

(Image credit: twinsburglibrary.org)

the West Nile Virus

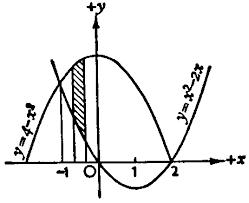

ScienceDaily (Dec. 11, 2009) — At least a dozen Alberta high-school calculus classrooms were exposed to the West Nile virus recently.

ScienceDaily (Dec. 11, 2009) — At least a dozen Alberta high-school calculus classrooms were exposed to the West Nile virus recently.

Luckily, however, it wasn't literally the illness. University of Alberta education professor Stephen Norris and mathematics professor Gerda de Vries used the virus as a theoretical tool when they designed materials for use in an advanced high-school math course. The materials allow students to use mathematical concepts learned in their curriculum to determine the disease's reproductive number, which determines the likelihood of a disease spreading.

"This piece was designed to satisfy an optional unit in Math 31 (Calculus), for which there are no materials, so we said, 'let's fill the gap,'" said Norris. "These materials show a real application of mathematics in the biology curriculum for high-school students."

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Our brain is wired to perform calculations that let us judge how far away an object is when we walk or jump around or reach for a container of milk. Although this task may seem easy, it turns out that calculating depth is surprisingly complex.

Our brain is wired to perform calculations that let us judge how far away an object is when we walk or jump around or reach for a container of milk. Although this task may seem easy, it turns out that calculating depth is surprisingly complex.

When we look at an object, our eyes project the three-dimensional structure onto a two-dimensional retina. To see the three dimensions, our brain must reconstruct the three-dimensional world from our two-dimensional retinal images. We have learned to judge depth using a variety of visual cues, some involving just one eye (monocular vision) and others involving both eyes (binocular vision).

Corresponding Article!

Your brain is doing some amazing calculations as you read these words. Not only are your recognising the letters, the upright and top cross of the 'T', but you are also understanding what they mean. Imagine if you could build a computer with the same kinds of skills? Computer Scientists are looking at how our brains work to build better machines. One area where people are far better than current technology is in seeing. Around half your brain is estimated to be involved in processing some type of information from your eyes.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Experiment indicates that infants recognize apparent errors in subtraction.

Next time someone complains about arithmetic being hard, math lovers can defend themselves by saying "even a 6-month-old can do it."

Next time someone complains about arithmetic being hard, math lovers can defend themselves by saying "even a 6-month-old can do it." Through monitoring the brains of infants, researchers confirmed that infants as early as 6 months in age can detect mathematical errors, putting to rest a debate that has gone on for over a decade.

A team of scientists from the United States and Israel exposed 24 infants to a videotaped puppet show. They used the puppets for addition and subtraction while observing the reaction of the babies.

For example, they started the show with two dolls. Before the show ended, a doll was removed and then the infant's vision was blocked with a screen. When the screen was taken away, either one doll was left, as expected, or two dolls, which would not be mathematically correct.

The infants looked at the screen longer (8.04 seconds) when the number of dolls was two, which did not agree with the solution of 2 – 1 = 1.

(Image credit: praisebaby.com)